We need to establish what we mean by immortality. The concept itself can be seen from two different lenses, that is both divine and worldly. Divine being the experience after death. This is much more literal. We can get an idea of the religious beliefs of the cultures from all four of these works. Worldly is fame among men. Which means that in asking the question we are asking what did these cultures value. Evidently enough what ideals people hold and those who embody them are going to be the most esteemed. While the Epic of Gilgamesh, Iliad, Aeneid, and Divine Comedy were written by individuals and don’t necessarily represent the entirety of the civilizations in which they originate from, along with them being fiction, we do not conclude they can teach us nothing. All four are both famous and highly praised works, read widely throughout their respective countries even in their own time. We are still reading them even up to today. I think a general statement we can make is that each conception of a hero is more subtle than the last. Societies developed new technology and as a result their ideas about the world changed. Gilgamesh had a desire to transcend life in a quest for eternal life. Achilles opted for an enduring legacy on the battlefield. Aeneas set the groundwork for an immortal lineage. Dante perhaps being the most complex, opting for spiritual salvation rather than worldly. As such, I think it would be fitting to explore both divine and worldly immortality, discussing all four of our protagonists in turn.

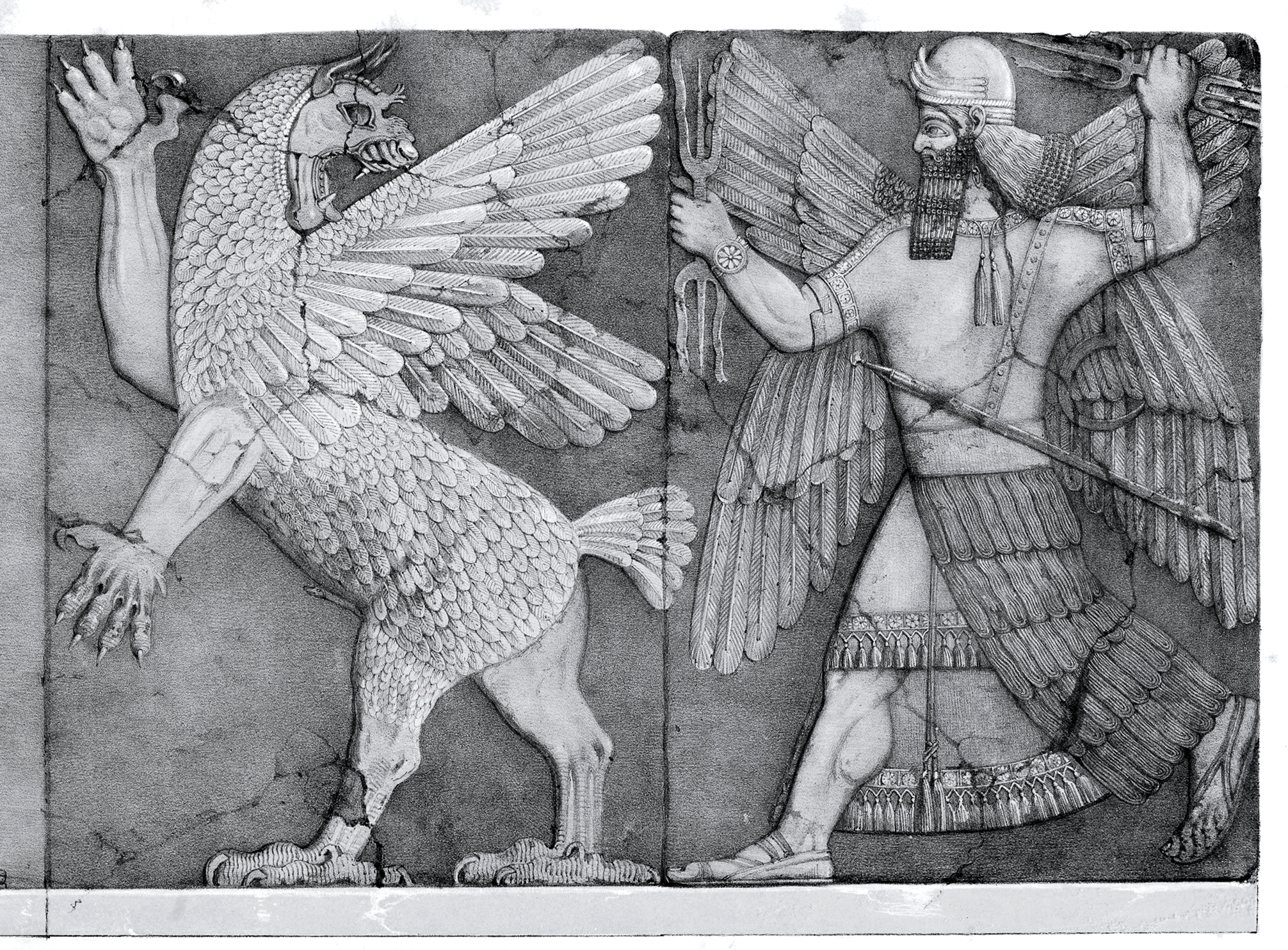

The Mesopotamians had a polytheistic conception of the divine, mostly connected with natural phenomena like the sky and the storms. The human race were believed to be made for the explicit purpose of serving the gods. Gods were imagined in human forms and had many of the same strengths and weakness which humans possess, but differing in their greater power, sublime position in the universe, and immortality. The Mesopotamians conceptualized death as being a gloomy place, where those confined to it were doomed to suffer perpetual hunger and thirst. No distinctions were made on how one lived in one’s life, everybody met the same fate. The Greeks similarly believed in a pantheon of Gods. The Greek view of death was a bit more comforting than the Mesopotamian one, but there still is a reason why Hades was seldom mentioned or given prayers to. The Greeks did believe your actions in your life will effect your place in the afterlife. If you were an extremely virtuous individual you would be sent to the Elysian Fields, which was a realm of eternal happiness and bliss; similarly, if you were extremely wicked you would be sent to Tartarus, a place of punishment and torment. Being sent to either was only reserved for the most virtuous/wicked men. Vast majority were believed to be sent to the Asphodel Meadows, were one passed a highly monotonous existence. The gods in The Aeneid are believed to be mostly to same to their Greek counterparts. There are differences, like Minerva being not so nearly as prevalent to the Romans as she was to the Greeks. The Inferno is a major shift. With Christianity sweeping over Europe, the conception of gods changes from a pantheistic one to a monotheistic model, with God being this all powerful, infinitely perfect being. The point of the epic being to show people what awaited them in the next life. In Christian belief the actions you take in your life have a much greater impact on your fate in the afterlife. While it is more comforting for the virtuous, it is more demanding and those who live wickedly can expect to face greater odds of punishment. A reminder that God is constantly watching and judging.

If we take what is written in the epic at face value we can read it in one way as almost hero worship. Gilgamesh is this being that transcends man. He’s a man who commands obedience from his fellow man while at the same time possessing strength enough to slay any foe he may encounter. In the beginning he is quite arrogant and seemingly he gives off the impression that he can accomplish anything on Earth, which he has been able to up until that point. It was when he witnessed the death of his friend Enkidu that he goes astray. Instead of aspiring to the limits of man he yearns for the privileges of a god. Though Gilgamesh was never outright criticized, in its stead the author makes use of irony. Gilgamesh wasn’t painted as an absolute hero and his actions are not always portrayed in a positive light. At the beginning of the epic we hear how he treats his people badly, not listening to the council of his advisors or Enkidu, his fear of death, and his foolhardy quest for immortality. All of which sheds light on Gilgamesh’s humanity and the framework within which we humans have to play by. The emphasis on domestic life, Gilgamesh is constantly reminded that the greatest joys of human life are to be found at home. For the epic both opens and closes with the line, “O Ur-shanabi, climb Uruk’s wall and walk back and forth! Survey its foundations and, examine the brickwork! Were its bricks not fired in an oven? Did the Seven Sages not lay its foundations?" (XI.327-330)

I think in terms of the heroes, Gilgamesh and Achilles share much in common. The emphasis again is put on individuals who are almost greater than life. The concept of the hero was quite important in Greek culture. The way in which battles are depicted it is as if one man can sway the course of the battle if courageous enough. Rare is much attention given to soldiers who are not important figures in the army. The sentiment is reflected when Odysseus reproaches the soldier, “How can all Achaeans be masters here in Troy? Too many kings can ruin an army—mob rule! Let there be one commander, one master only, endowed by the son of crooked-minded Cronus with kingly scepter and royal rights of custom: whatever one man needs to lead his people well.” (2.234-239) The Greeks worshiped human heroes along with the gods. These heroes were both real or legendary, who came to command respect through great deeds and gained immortal status. Time and time again we see just how important reputation is to the Greeks. To be an object of great shame is almost a fate worse than death. The poem itself is ultimately about Achilles. He was given a warning by his mother that if he were to go in to battle he would not return. In spite of this he went and won immortal fame because of his actions.

The Iliad and The Aeneid share the greatest resemblance to each other. Not just in terms of Gods, but in terms of customs as well. Virgil was a poet employed by the Roman state. A motivating factor for writing it in the first place was for Rome to have her own creation myth. Tracing her lineage back to Troy was supposed to bring prestige and inspire pride. Aeneas himself as a character is much closer to dynamic Odysseus than the headstrong Achilles. The Iliad was much more concerned about the story of a single person. Aeneas does great deeds, but the full fruits of his labors were going to come about centuries after his death, his lineage. His personality is one that is very much devoted to both his family and the people whom he is leading. He made sure to carry his father out of Troy and held games to his honor at his death. In general, Aeneas leaves the impression that he is a more modern character. The world of the The Iliad contains many archaic aspects about it.

The Inferno is a great departure from the previous three because it is a large shift away from classical culture. With classical heroes it was all about the individual. The value of your person depended on the exploits which you could accomplish. Dante in The Inferno is much more complex. There is much more humility and awareness of the limits of human action. While it felt like with classical culture there was a constant pushing of limits, and this courage was celebrated and sung by the poets. What Dante is more concerned with is not goods of the world, but what comes after. The idea of redemption is crucial. We see how the soul was believed to be immortal, made up of a separate substance from the body. When you died you were to be sent to be judged. This ruling placing you in your suitable place in the afterlife. The futility of attempting to run away from God, since he sees and observes every thought and action. Going much beyond the the Epic of Gilgamesh where everybody meets this gloomy death, no matter how high you were in life, if you sinned you were to be punished alongside those who committed similar acts. The idea of the choices you make in life having eternal consequences is what it means. The reason for the punishments is to inflict pain, but pain is not the end goal. Above the gates to hell the words written are, “I am a creature of the Holiest Power, of Wisdom in the Highest and of Primal Love. Nothing till I was made was made, only eternal beings. And I endure eternally. Surrender as you enter every hope you have.” (3.5-9). The punishments are in proportion to the severity of the sin. No matter how great your sin, the necessity of repentance and the reunification with God is what underlies the meaning of the punishments to be found throughout hell.

The question of immortality is one that is and will probably forever be of pertinent interest for us. Thomas Hobbes gave three reasons why humans are perpetually getting into conflict: them being 1) fear of death, 2) desire of that which you do not have, and 3) a wish to be acknowledged by your fellow man. Some even say that philosophizing is preparing oneself for death. In all four of these epics death was a central theme. You can begin to ask questions. Is fame a kind of immortality? How high of a price should one pay for such fame? Does it matter if people will remember you? What good does fame do when you are dead? The famous line by Achilles in the Odyssey goes, “No winning words about death to me, shining Odysseus! By god, I’d rather slave on earth for another man / Some dirt-poor tenant farmer who scrapes to keep alive—than rule down here over all the breathless dead." (11.555-556) While odds are we shall be coming to no proven conclusions anytime soon, exploring the concept maybe brings us just that much closer to what it means to be human.

Sources:

Alighieri, Dante, and Robin Kirkpatrick. The Divine Comedy. Penguin Books, 2013.

George, Andrew. Epic of Gilgamesh. Penguin Publishing Group, 2003.

Homer, and Robert Fagles. The Iliad. Penguin, 1998.

Kagan, Donald, et al. The Western Heritage. Pearson Education, 2011.

Virgil, and Robert Fagles. The Aeneid. Penguin, 2010.