I’m not entirely entirely sure if these verses were the inspiration behind the title of this movie, but given that in the funeral scene Christian hymns appear to have been sung, it would certainly make sense.

To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven: A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted; A time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to break down, and a time to build up; A time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance; A time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together; a time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing; A time to get, and a time to lose; a time to keep, and a time to cast away; A time to rend, and a time to sew; a time to keep silence, and a time to speak; A time to love, and a time to hate; a time of war, and a time of peace. What profit hath he that worketh in that wherein he laboureth? I have seen the travail, which God hath given to the sons of men to be exercised in it. He hath made every thing beautiful in his time: also he hath set the world in their heart, so that no man can find out the work that God maketh from the beginning to the end. (Eccl 3:1-11)

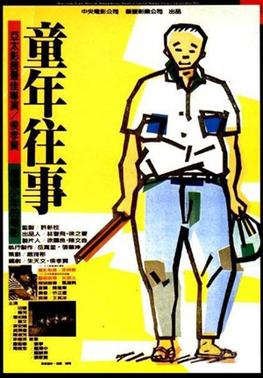

A Time to Live, A Time to Die is a Taiwanese film that was released in 1985. The movie was directed by Hou Hsiao-hsien. It’s a movie that I believe is difficult to explain because it’s one of those movie where it’s not so much about what the movie says, but what is left unsaid. Often times I feel movies like this, created by men of meager talent, can degenerate into pretense rubbish. One good example of this, also a Taiwanese movie, is Goodbye, Dragon Inn. The quintessential critic film to fill their columns about how sophisticated they are that they can sit through such a dull movie with nothing to say. If one were to enumerate the themes of this movie I’d think they’d be: transience, sacrifice, family, death, youth, old, new, inevitability, and poverty. To me this movie feels more Japanese than Chinese, even down to the house (which I believe is a Japanese style house, probably left over from the Japanese occupation).

A summary of this movie in one sentence would probably be: family on losing side of Chinese civil war goes to Taiwan and makes the most of their circumstances. This is a movie for a specific audience, an older generation of Taiwanese (with that word encompassing those who moved from mainland China) who either lived through the war or grew up under the consequences of it. If you’re not part of that demographic then this movie may be a bit difficult to relate to. It’s an in-between generation, one that is very strongly culturally Chinese, but has no part in the People’s Republic of China. A generation which possesses many of the traditional Chinese values, yet is alienated from it. Younger Taiwanese are very often quite Westernized. It so happened that it came about for me that I’ve been surrounded many such people, I can see the difference in their kids. Almost like White Russians who had fled Russia. Little future, a future in which they can survive, but one they can’t quite fully consent to. I believe this to be key to understanding the feelings of those who came to Taiwan and those who were raised by such people.

This movie is not technically complex. It doesn’t make use of CGI, doesn’t have any quick moving action scenes, no complex editing, no complex cutting, and no complex moving camera. Whether it was due to budget or individual taste on the part of the director, this movie is very personal and grounded. It’s the same with the sounds that appear in the movie. There exists nothing in this movie that resembles examples of sound such as the one given in the book of asynchronous sound with Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps and the train. This matches the mood of the film because this movie doesn’t have a great climax or even much of a plot. I feel this way of storytelling is a bit foreign to Western audiences. Usually when we read some kind of book or watch a movie we expect a beginning, middle, and an end, we expect something to happen—we expect a hero’s journey. There’s a famous Japanese novel that’s called the Tale of Genji. The translator of the deluxe Penguin edition Royall Tyler in the introduction of the book described it like this:

The narration is never in a hurry, and it follows interweaving, indirect paths that may break off only to reappear later, like a stream that sometimes flows underground.

He goes on to say,

Moreover, the narration often juxtaposes elements and scenes rather than stating a connection between them, leaving it up to the reader to see and define the relationship between one thing and another. The moments or scenes juxtaposed this way are not necessarily adjacent to each other. They come together, if they do, only in the reader’s mind, thanks to memory and association encouraged by repeated reading, and the connection is seldom demonstrably intended because the narrator says nothing about it.

A very long book clearly divided up into chapters is more effective for creating such an atmosphere, but roughly the sounds of this movie needs to create an atmosphere such as how Mr. Tyler describes. I would like to look at 18:07 to the end of the scene.

The scene begins with us looking radio at the radio. The radio is presenting what appears to be a propaganda government broadcast. (I define propaganda as anything that is short and easily understood, is repeated ad nauseam, and sets out to convince the audience of a viewpoint.) The sound is originating from the radio and the radio is clearly in the frame. The sound coming from the radio is diegetic and on screen. While the radio is the main focus of the camera, we hear no other sounds. I feel as if I should quote a little from the radio, so you can understand the environment and the contrast which is going to be drawn.

Hot news. In an air battle today over the Matsu Straight, our courageous Air Force pilots downed 5 communist MIG 17’s and damaged two others. This glorious combat will serve as the greatest gift to all of our country men on this Double Tenth National Day. Despite being outnumbered, our courageous Air Force pilots were determined in combat, glorifying the spirit of revolutionary battle. They have won the hearts of all our countrymen. In particular, Colonel Chang Nai-chun. In the heat of combat, to save a nearby aircraft from enemy fire, thinking not of himself, he rammed his plane into a Communist craft. His patriotic and glorious sacrifice has once again glorified the revolutionary spirit of our forefathers, the spirit of sacrifice and struggle, writing down the most glorious page in our Air Force history.

Listening to this you get an idea on why the Chinese peasants largely sided with the Communists. This was the first item. The radio again goes “Hot news” and we hear,

President Jiang announced the victory of the airwar…

The reaction of the family is indifference. The intention I had of quoting from it verbatim is that you can sense the militarism and the increasingly empty voice coming from the radio. When you know you’re being lied to in the beginning you might feel indignant, that’s a healthy and good response. Unfortunately, when an individual has been told the same lie often enough, even if he knows it’s wrong, at a certain point it just becomes indifference and those feelings of indignation begin to dull. This appears to be the situation with this family’s reaction to the news broadcast. It’s little more than white noise to them.

While the news broadcast is playing, the camera cuts and is now on the family. The radio is still diegetic, but now its offscreen, making it offscreen sound. The radio exists in the world and can be heard by everybody in the room, so it’s external sound. So far, we can’t hear any ambient noise. We begin to hear other sounds. The biting on what appears to be some kind of vegetable produces a sound. After that we can then hear another noise, one that a trained ear could probably immediately recognize as a sewing machine. With the sewing machine we can now hear birds chirping too. The length of time between between the start of the radio broadcast and the first character to speak is around one minute. The chirping of the birds is ambient noise. The sound of the sewing machine is not because we will see it in a shot of the mother sewing while talking to her family, so it is not an item which is in the background. A dialog proceeds with the family, ending and going on to a different scene at around 21:27. The dialog is calm, but its melancholic and fatalistic. Talk of sad events in such a casual way is a display of their hardship and a testament to their experiencing such things and their adapting. At around 20:00 the news broadcasts ceases and military music begins to play. The sound is loud enough to clearly discern, but quiet enough to still feel the tranquil environment and lazy atmosphere in the house.

These sounds in this scene are largely to evoke two contrasting sentiments from the viewers. On the one hand we have the news broadcast telling of good news that doesn’t appear to be reflected in the family’s life. The music after the broadcast represents the arts of man. The other is a tranquil family scene with everybody gathered and occupied with something. The birds chirping is peaceful and represents nature. The chomping from the snack which the father and the kids are eating adds to a peaceful environment. The sewing which the mother is engaged in as well. It’s the contrast between these two that the director has created, largely thanks to sound. The emotions of the characters is easy enough to perceive, but it is never said. The conversation appears relatively mundane. This scene accomplishes three main objectives simultaneously, it provides background information, conveys the emotions of the characters, and gives an idea of what hardship and bad luck this family has endured.

I think some of the most beautiful shots are in the section of the movie where the grandma takes the youngest boy back to the mainland and she finds and place that is changed. The locals don’t understand her and the landmarks she remembers from her younger years are no longer there. This scene runs from 43:30 to 47:51. This movie is shot pretty standardly with a 1.85 aspect ratio and at 24 frames per second. An aspect ratio of 1.85:1 is called American widescreen. 1.85 is common for modern commercial, widescreen releases. 24 frames per second was a standard set back in the 1920’s, and this movie doesn’t deviate from that. The first shot of this sequence is where we see grandma and Ah-hao (阿孝, nickname for the boy) setting out. The director uses a long shot because he wants us to see and follow the pair’s trip, but it also establishes distance and scenery. In many of these shots leading lines are a crucial component. Here it’s the road. You can also notice about how the camera isn’t located in the middle of the road, but to the side. The road doesn’t start in the middle of the shot, it’s only when the road has gone on for a bit from where the camera is located that it is centered, and since it’s farther away it’s smaller. Leading lines are both aesthetically pleasing and guides our eyes.

The next shot is of another road that leads to a railroad crossing. I would call this an extreme long shot because the goal of this shot isn’t to show a subject, the two of them are only visible in this shot if you know exactly where to look and pause the video. We have another leading line with the road. This line leads our eyes to the train which is about to pass by and put the traffic to a halt. The two of them are at the small restaurant which could be seen in the previous shot. The camera cuts and now we have a medium shot with both grandma and Ah-Hao sitting at the table. We can notice the camera is at eye-level, but it’s not at the level if they were standing. The eye-level is relative to them sitting at the table. The same train that the previous shot had drawn our attention to is still rolling past in this medium shot. Now we see the railroad tracks. This is another extreme long shot. Employing yet another leading line with the tracks. Cut back to the restaurant and it’s still a medium shot, except what we have now is two other people in the frame. Predictably, a dialog starts and the younger woman who could hardly be seen in the beginning comes over to engage in the conversation.

We leave behind the restaurant and now the two of them are walking down a country road. This is a long shot because the director clearly wants us to make out the two figures on the road. Again, the road is used as a leading line to guide us to the two walking on the road. Grandma and Ah-Hao walk down the road and approach the camera and we watch then picking guavas. There is actually no cut here, the camera simply pans right. I feel it’s a bit difficult to tell because it’s subtle, but I don’t believe a handheld camera was used. The movement is smooth. A cut again and we see the guavas being washed and, later on, attempting to juggle the guavas. Here a long shot is used because the director wants the audience to see all three people in the frame. With the activities and setting established, the scene cuts and now there’s a medium long shot of grandma and the young boy playing with the guavas. Since we already know the background, the director can now focus in on the movement. The closer camera gives a more intimate feel between the young boy and older woman playing with the fruit.

Probably, for most of us (Americans), this film isn’t too important or relevant. Yet, I’m sure for the 外省人 (Japanese is gaishoujin and Chinese seems to be wàishěngrén) and their children this film is probably quite relatable. I don’t think this movie set out with the intention to make some grand statement. One of the themes carried throughout this whole movie was that what surrounds us is so much greater than ourselves. Society will largely not care whether an individual lives or dies. In contrast, our lifespans appear quite short and us quite frail. There’s so many lessons that one could pick out. For example, what the grandma represents. She represents a woman who never quite adapted to a changing China, the old attitudes and the new. When she goes back to the mainland she finds that people can’t understand her. At one point she talks about how women don’t need education and only need to know the “three bottoms”: bottom of a wok, bottom of a needle, and the bottom of a field. She outlived both the father and the mother. When she died it took the family some time to recognize she was dead. When the undertaker came he gave them a look rebuking them for their negligence and lack of filial piety. When she died she represented something old and forgotten, something possibly grand at one time but bound to be lost in the cruelty of time. She represented the closing of an era in Chinese history.

The sister is forced to sacrifice herself after her father died. The family, already poor, lacked money so she was told by her mother she needed to become a teacher. She had wanted to go to a Girl’s High School in Taipei. This essentially meant a bleak future for the young woman. She was tethered by her family because there was no better choice. A bleak and tedious future, one where a good marriage doesn’t seem likely. One where one’s youth is spent doing menial chores, not being able to enjoy her life because of her family’s poverty. The way which she stoically accepts her fate, developing the virtues that come out of such a lifestyle. More than the deaths of her father or mother or grandmother, I think I found her most tragic of all. There was no room to complain because no one was in the wrong. Simply a combination of defeat and bad luck, an example of the unfairness of life. Reality isn’t like the movies, some people are hardly given a chance.

Yet, all of this is secondary. What this movie focuses on above all is family, particularly the pain which a family brings. As a depiction of a Chinese family it is feels painfully accurate. It’s particularly painful because it’s believable. Dealing with the struggle of existence, the movie is cruel because life is cruel. As a society we tend to despise death and attempt to sort of drape a blanket over it. We focus on growth and blush at degradation. This movie doesn’t shy away from depicting both life and death. In this movie I believe there to be an almost equal amount of life and of death. We see not just struggles with disease and old age, but youthful ones as well. They exist side by side. They have existed for thousands of years. I think life and death’s coexistence, along with that which is depicted on screen being only a drop in the bucket of that endless struggle for life, is this film’s ultimate message.